A sealed move reshapes the Iran-Contra case

Behind closed doors, the grand jury examining the Iran-Contra affair quietly put three familiar names in a new legal category: unindicted co-conspirators. According to sources close to the investigation, former National Security Council secretary Fawn Hall, ex-NSC official Robert Earle, and former CIA officer Joe Fernandez have been designated as such under a court order that remains sealed. It’s a technical-sounding step with big trial consequences.

Here’s why it matters. Independent counsel Lawrence E. Walsh is building a conspiracy case against four defendants—Oliver L. North, John M. Poindexter, Richard V. Secord, and Albert A. Hakim—over the alleged diversion of profits from U.S. arms sales to Iran to the Nicaraguan Contras. By naming Hall, Earle, and Fernandez as unindicted co-conspirators, prosecutors can try to use their out-of-court statements against all four defendants at once. In a standard case, a witness’s statements usually apply to a single defendant. In a conspiracy case, statements made during and in furtherance of the alleged scheme can sweep more broadly.

That’s the co-conspirator rule at work—the hearsay exception prosecutors love in complex cases. In practice, it means notes, memos, or conversations attributed to Hall, Earle, or Fernandez may get in front of a jury not just as their recollections, but as admissions tied to the alleged joint effort. Defense teams know this changes the terrain, and they’ll almost certainly push back, arguing these statements don’t meet the strict test of being made during and in furtherance of an actual conspiracy.

The move also signals how close these three were to the center of activity. Hall worked as North’s secretary from 1983 to 1986 and became a central figure after she told Congress in 1987 that she altered and shredded documents and even smuggled papers out in her clothing. That’s when she famously said, “Sometimes you have to go above the law.” Two years later, she received immunity in exchange for her cooperation in the criminal case against North. Earle, a former NSC aide who sat just outside the spotlight, kept records and saw operations unfold up close. Fernandez, a onetime CIA station chief with firsthand knowledge of Central American operations, was tied to field-level logistics and contacts.

All of this sits atop the core allegations: that money from covert arms sales to Iran—during a period when the U.S. publicly denounced Tehran—was steered to the Contra rebels despite congressional restrictions, known broadly as the Boland Amendment. North and Poindexter have long maintained they acted to advance national security priorities. Secord and Hakim, private operatives tied to what was often called “the Enterprise,” allegedly helped keep the supply network running when official channels were closed.

What it means in court—and what could derail it

Labeling someone an unindicted co-conspirator doesn’t mean they’re being charged, and it doesn’t guarantee a courtroom win. It’s a legal tool aimed at admissibility. Under the co-conspirator hearsay exception, prosecutors must first show a conspiracy existed and that the person making the statement was part of it. Judges usually require proof by a preponderance of the evidence before letting the statements come in. Expect a fight over each piece of evidence, with defense lawyers challenging timing, context, and whether a statement actually advanced any agreement.

There’s also a fairness question baked into this move. People named as unindicted co-conspirators get no chance to defend themselves in a full trial, yet the label carries a stigma. It can shape the narrative in the courtroom without the due process protections that come with a formal indictment. Prosecutors see it as necessary; defense teams call it prejudicial. Judges try to thread the needle by holding pretrial hearings and limiting how and when such statements are used.

Classified information is the other looming problem. Parts of this case reach into intelligence operations, which means secrets. Prosecutors have to build their case without spilling sensitive sources, methods, or diplomatic tradecraft. That’s where the Classified Information Procedures Act (CIPA) comes in. It allows judges to review sensitive materials privately and, when possible, substitute summaries or redactions rather than reveal raw intelligence. But if critical evidence can’t be sanitized, charges can falter. That risk isn’t theoretical—national-security prosecutions have unraveled before when agencies refused to declassify what a jury would need to see.

Fawn Hall’s history adds another wrinkle. She’s already on record saying she shredded and altered documents tied to this very web of activity. Prosecutors want to use that proximity to show how the operation shielded itself from scrutiny. Defense lawyers will counter that her actions were chaotic cleanup, not proof of a shared criminal plan. They’ll also question her memory, motives, and the impact of her immunity deal on her credibility.

Robert Earle’s role is more procedural but still potent. Aides who keep calendars, memos, and notes can end up being the backbone of a conspiracy case. Paper trails—who met when, who approved what—are the connective tissue prosecutors use to argue there was agreement, not just parallel actions. The same goes for Joe Fernandez. Field officers often know which shipments were aid, which were arms, and which were something else entirely. If Fernandez’s statements are deemed part of the conspiracy narrative, that’s a direct line from Washington planning to activities on the ground.

This is why the stakes are high for North, Poindexter, Secord, and Hakim. A conspiracy case rises or falls on whether the government can paint a coherent, coordinated picture. If jurors see only a messy blend of policy improvisation, interagency confusion, and private freelancing, the case weakens. If, instead, prosecutors show a system—money in, arms out, reports massaged, records trimmed—then the co-conspirator statements become the mortar between the bricks.

To understand how we got here, rewind to the mid-1980s. Congress pulled back direct military aid to the Contras. Meanwhile, the Reagan administration was searching for ways to free U.S. hostages held by groups tied to Iran. A clandestine pipeline took shape: arms to Iran, funds diverted to the Contras, and a small circle managing the flow. The Tower Commission report and the 1987 televised hearings exposed the broad outlines. The criminal cases are where those outlines get tested against the evidence rules.

Walsh’s team has to juggle three tough tasks at once: secure admissible evidence, protect classified material, and win the argument that what happened wasn’t just bad judgment—it was a criminal agreement to defraud the United States. The conspiracy count frames the diversion of funds as a scheme to evade federal law and mislead the government, not just Congress. If jurors accept that framing, the unindicted co-conspirator designations could act like a bridge, letting statements from Hall, Earle, and Fernandez carry across to all four defendants.

Defense teams will aim to chip away piece by piece. Was a given statement made “during” the conspiracy, or after the fact? Did it “further” any shared plan, or was it knife-and-fork bureaucracy—people explaining, venting, or trying to manage fallout? They’ll challenge the government’s timeline, argue that policies came from the top and shifted quickly, and insist that private actors like Secord and Hakim ran their own show.

One more thing to watch: the credibility math. Jurors often weigh a witness’s deal—like Hall’s immunity—against the gravity of their testimony. The government will say it needed insiders to tell the story. The defense will ask why those insiders aren’t on trial themselves if the case is as clear as prosecutors claim. That tension sits at the core of many conspiracy trials, and it will be front and center here.

For now, the sealed designations tell us where prosecutors think the story leads. They point to a tight circle, acting in concert, shielding itself from oversight, and moving money across a legally closed bridge. Whether that story clears the high bar of the courtroom will turn on rules that sound technical but decide everything about what the jury hears—and what it never will.

- Oliver L. North: Former NSC staffer accused of helping steer funds and manage operations outside normal channels.

- John M. Poindexter: Former national security adviser, charged with overseeing and approving key decisions.

- Richard V. Secord: Retired Air Force general connected to the private logistics network known as “the Enterprise.”

- Albert A. Hakim: Businessman and Secord partner, tied to the money trail and procurement lines.

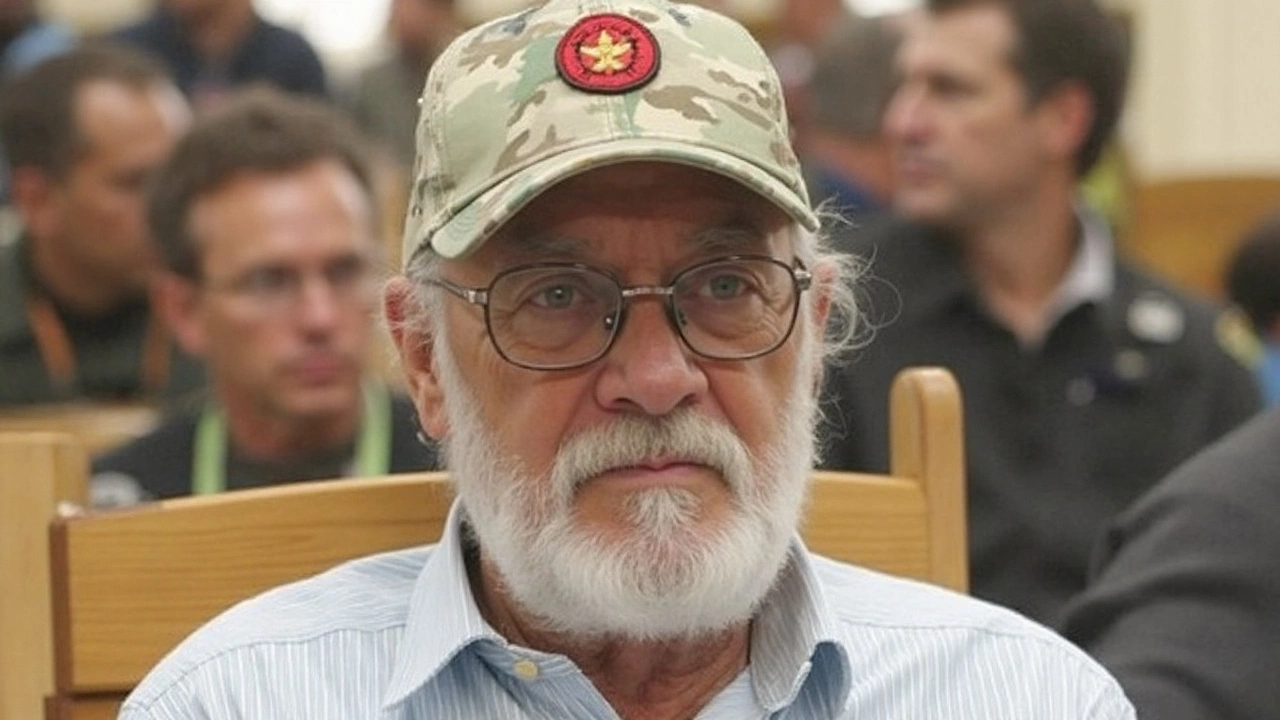

- Fawn Hall: North’s secretary who admitted shredding and altering documents; later received immunity in exchange for cooperation.

- Robert Earle: Former NSC official whose records and proximity could anchor the timeline of events.

- Joe Fernandez: Former CIA officer with on-the-ground knowledge of Central American operations and supply routes.